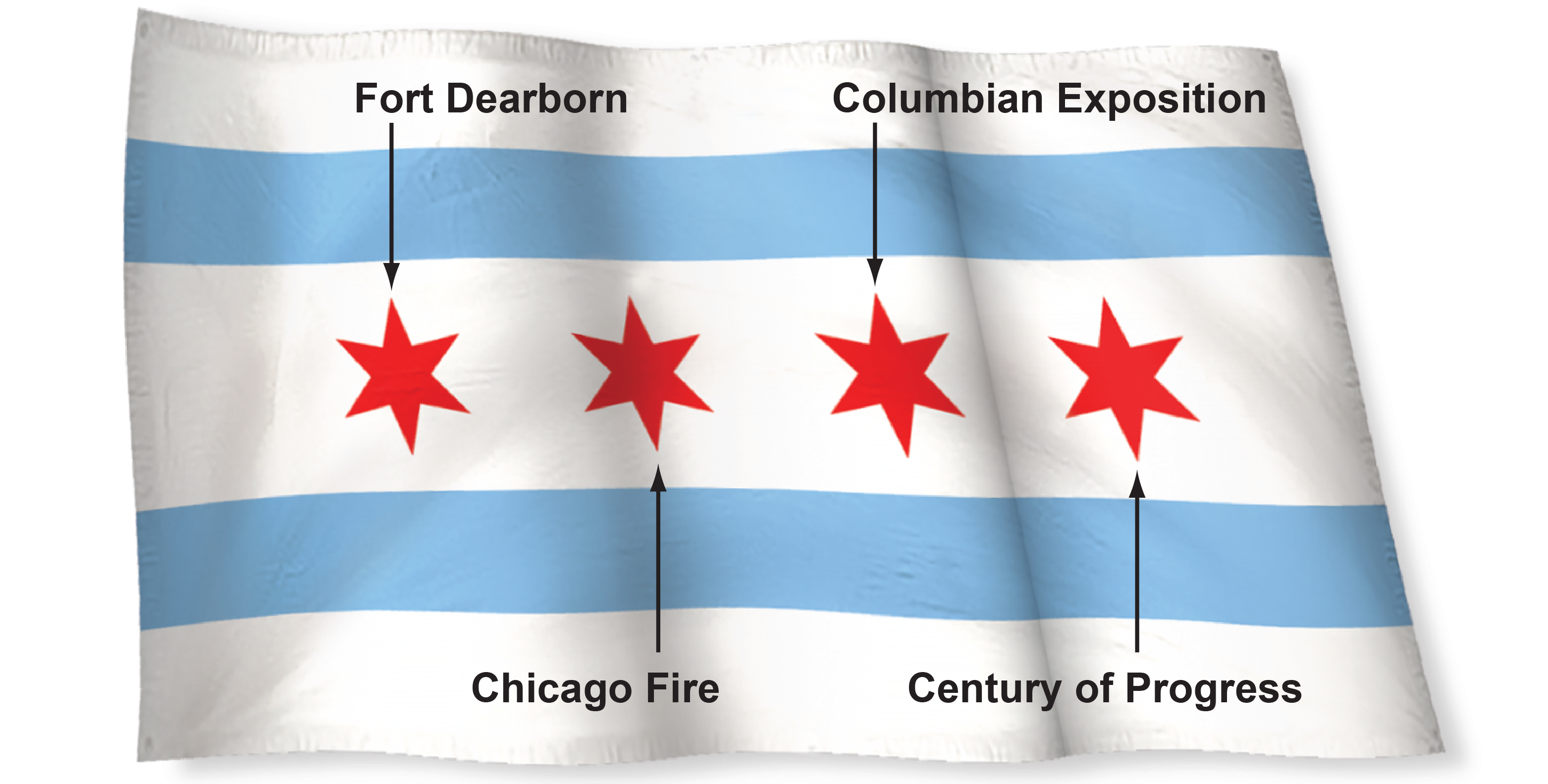

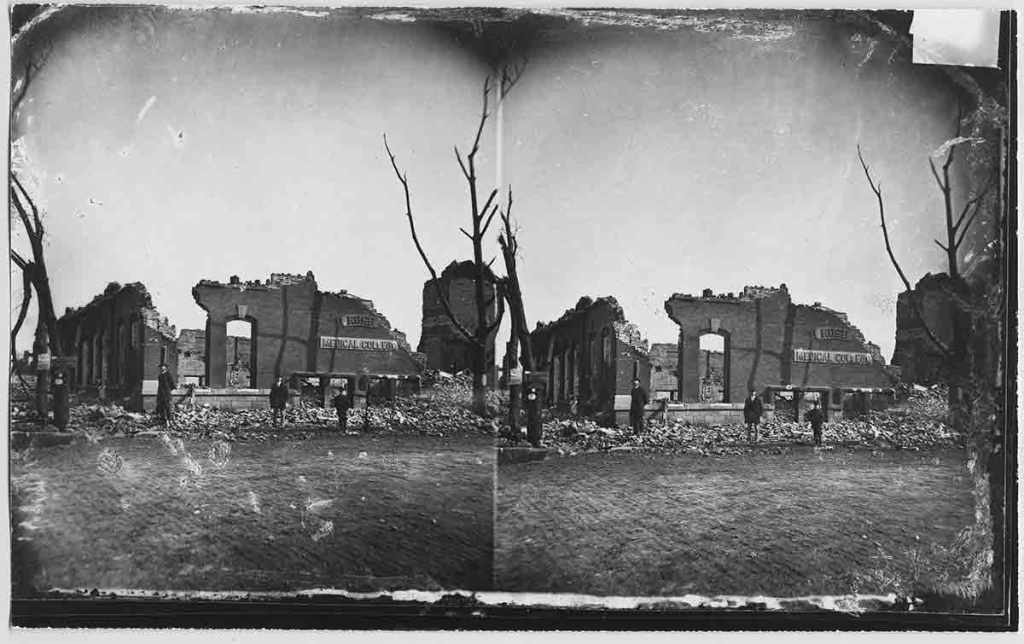

For those unfamiliar with this bit of history, there was a catastrophic fire that pretty much leveled the city in October of 1871. It started on the West side, and lept from neighborhood (not street, NEIGHBORHOOD) to neighborhood, eventually engulfing a jaw-dropping 2/3rds of the city a couple days later. The fire devoured wooden houses, barns, and lept city blocks, while exhausting all the fire fighting resources (think steam-pump fire engines and horse-pulled carts). Legend has it from Lake Michigan, all you could see was a horizon on fire. As the smoke cleared, 100,000 people were left homeless (about 3 in every 10 people at the time). The official death toll is somewhere in the hundreds, but probably inaccurate as many of the deceased were never counted actually – as they may have been incinerated or drowned. Today, this disaster is remembered in the second of the four stars on the Chicago flag.

Recovery Efforts

Immediately after the fire, donations began to pour into the city from all across the nation. New York City sent around $500,000, St. Louis gave around $300,000. Trains arrived with clothes, fire fighting equipment, food, books, etc. The Relief and Aid Society was established from a makesh/ift committee of volunteers that did an exceptionally well job successfully organizing the city’s distribution of food and supplies.

However, as with every disaster, there were those that took advantage of the situation. Along with the fear of theft and looting came actual professional thieves, who traveled to Chicago to take advantage of the desperate conditions. Chicago’s Mayor Mason declared martial law, hiring a former civil war veteran to oversee the implementation.

Forcing The City’s Hand at Policy Changes

Devastation quickly turned to anger, as the citizens and politicians searched for someone to take the blame. The Chicago Tribune said the city had not learned their lesson, calling for an increase in the fire protection laws. In response, the Citizens Association of Chicago began enforcing metal fire escapes in residential buildings more than three stories high. Fireproof walls were required between buildings. The use of wood was entirely banned downtown, and brick, limestone, marble, and terracotta were used instead. This also served as a class divider for those poor migrants who couldn’t afford to rebuild with anything but cheap wood – leaving the more wealthy even able to rebuild downtown.

The Black Community and The Forgotten Fire of 1874

Parts of the city that housed mainly Black populations were not greatly affected by the Chicago Fire of 1871, however, there was a second fire that hit those neighborhoods very shortly after, in 1874. This is a forgotten piece of history. This was a one-two punch for a large part of the black community. 85% of the Black owned property was destroyed (most of which was by the lake). This as well as anti-black racism heightened by the scarcity of resources led to the Black community moving closer together – many moved south, forming what’s now known as Bronzeville and Chatham. Self-reliance and the segregation Chicago is infamously still known for, is due in large part because of the hard times following the second fire.